BRAZIL'S FAMILY HEALTH STRATEGY

Text by Jeremy Ravinsky

Photographs by Paulo Souza

Video by Débora Klempous

On a sunny afternoon in August, Marcia Victor da Silva Acquino climbs a steep staircase to Ladeira dos Tabajaras. The favela is built across a mountain face stretching from Copacabana to Botafogo, hovering above Rio de Janeiro’s most famous beaches. Even in winter the midday sun is parching. But Marcia’s ascent is shielded from the heat by the surrounding foliage, casting cool shadows over her path. As she makes her way up the damp stone steps, the noise of traffic below recedes.

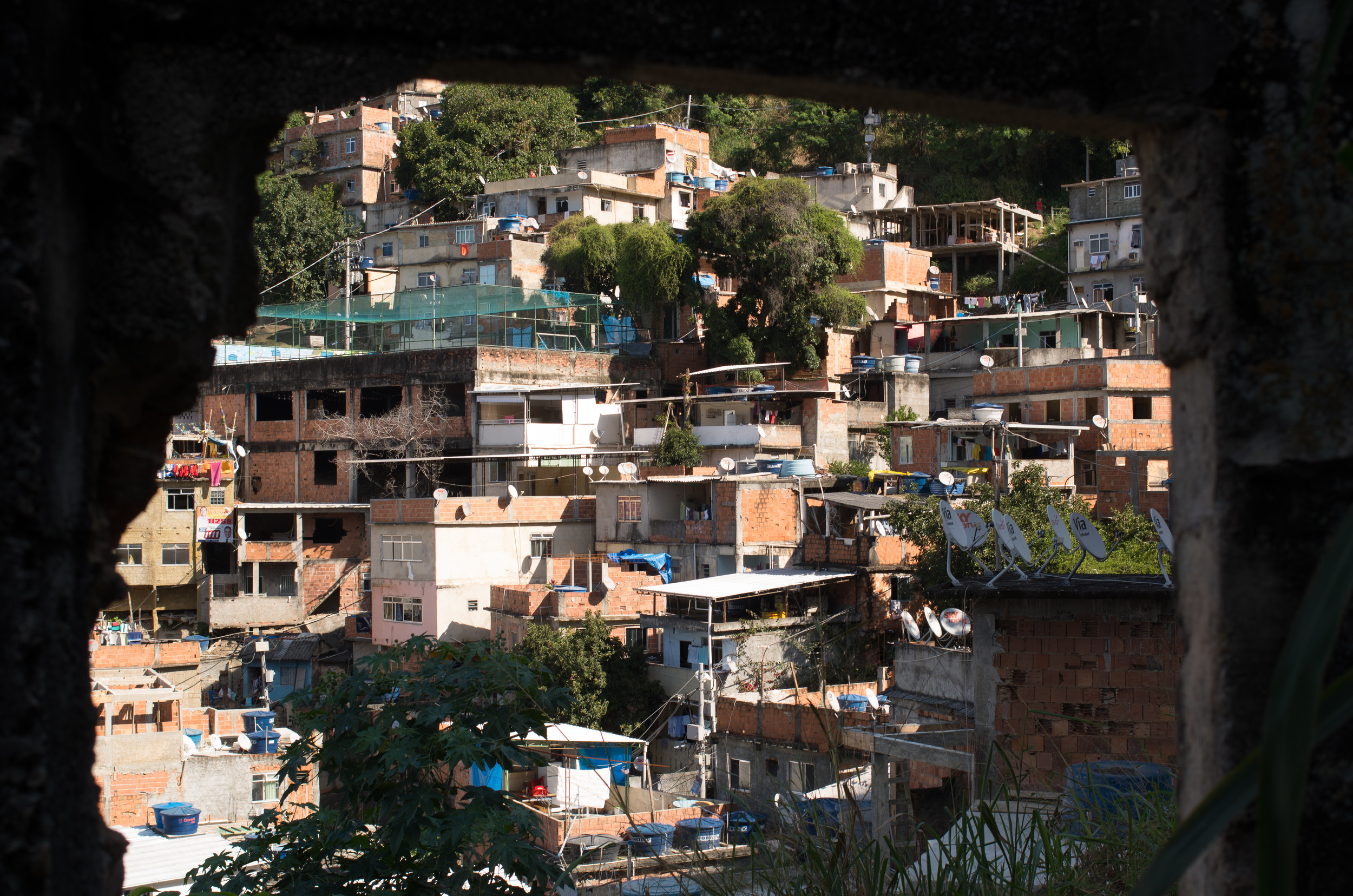

Tabajaras is one of Rio de Janeiro’s thousand favelas – urban slums often built vertically along the city’s mountains. In the valley below, the busy streets of Copacabana, one of Rio’s most expensive neighborhoods, stretch out to the ocean. Locals sunbathe while children splash carelessly in the shallows, their joyous shrieks smothered by the crashing tide. Tourists, sun-screened and shirtless, sleep in the sand or amble along Atlantic Avenue. Past the beach, street after street is lined with expensive restaurants, fancy hotels, and pricey boutiques. Men in orange jumpsuits sweep the streets as throngs of pedestrians stampede by, outpaced only by the bustling traffic.

A mere five-minute walk away, the busy scene gives way to a different side of the city. Leading up to Tabajaras, the road curves and steepens, and the architecture of luxury condominiums abruptly turns to red brick, crude mortar, and corrugated metal. Graffitied concrete walls guard the residences beyond with rusty barbed wire or broken glass. Narrow staircases cut haphazardly through the dense thicket of buildings, connecting the houses above to the community’s main commercial artery.

Marcia lives off the main thoroughfare, in a dim two-bedroom apartment with her husband and their eight year-old son. The white walls reflect the glare of the small fluorescent bulb hanging from the ceiling in the living room. The adjacent room is the kitchen, equipped with a fridge, small stovetop, and a metal sink.

Living in Copacabana comes with certain advantages. “We have a lot of benefits,” says Marcia, “because you can go down and have a good hospital. There’s a UPA unit [emergency medical services]. You’ve got good restaurants.” But living in an expensive area of the city also drives the cost of living up. “When it comes to rent price, as down there becomes more expensive, it becomes more valuable here also,” Marcia explains. “Before the World Cup, the price of the buildings down there rose a lot. They became three times higher, much more expensive. So nowadays you can’t find anything really cheap. The rent up here is also expensive, and we that live here are suffering with it.”

Born in Tabajaras, Marcia has lived here her whole life. “My grandmother came here when she was young,” she says. “My mother was born and raised here.” When she reaches the houses at the top of the stone steps, a green metal door swings open, releasing a small pack of dogs, yapping and barking to greet her. An elderly woman in a yellow cardigan appears in the doorway. She walks over to Marcia and they embrace.

“She knows my family, my mother,” Marcia explains. “My aunt is the same age as her.” Marcia smiles affectionately at her friend, patting her on the arm as they chat briefly.

Marcia’s status as a local isn’t the only reason she’s so popular around Tabajaras. As her shirt announces to all who encounter her, Marcia is an agent communitario de saude – a community health agent, an integral part of public health services in Tabajaras.

“I used to be a shy person. There were a lot of people I didn’t talk to. Because of this job, I had to change my comportment because I am no longer a common resident. Today people have a lot of affection for me. ”

In poor communities around Rio de Janeiro, residents’ primary health care comes in the form of the Family Health Strategy. Part of the state’s Unified Medical System (SUS), the Family Health Strategy provides services to specific neighborhoods and communities, with a small group of medical professionals responsible for the medical needs in each one.

Each medical team consists of a general practitioner, a nurse, a nurse’s assistant, and an oral surgery team, along with six community health agents. All the agents come from the communities they serve. It is this feature that makes the program special: rather than have people come to the clinic, the agents bring primary health care to the patients’ homes.

Community health agents liaise between the clinic and the community by routinely checking in on families, scheduling appointments with doctors, and providing residents with a medical authority they can rely on. “They have me as a real reference,” says Marcia. “I am a health agent twenty-four hours a day. I am the health agent in the market, at the beach, at night, wherever my patients stop me and ask things. So I stop and give them the information they need, because you can’t restrict the attention you give to Monday through Friday, from 8 am to 5 pm.”

Part of the government’s effort to expand access to public health to communities with poor access to medical services, the Family Health Strategy is responsible for one hundred percent of Tabajaras’ residents having access to primary healthcare. But the fledgling public health system in Brazil still does not have the capacity to handle the needs of the whole population.

“I have 191 families, almost 500 patients,” says Marcia. “There are some priorities. The hypertension, the diabetics, pregnancies, children younger than a year old, tuberculosis patients… These are the most important groups. The others we can only visit once every three months, six months, even a year.”

Marcia has been a community agent in Tabajaras since the program was implemented almost four years ago. “I heard about the selection to be a health agent. It interested me, so I applied. It was new thing that was happening here. I entered the first team, right at the beginning.”

The agents work in shifts, one in the morning and one in the afternoon. They must visit a minimum of six patients during their rounds. Normally, Marcia does her visits alone, but today Andressa Balsan, a nurse from the clinic, accompanies her on her afternoon shift.

One of Marcia’s patients is Cassia, a mother of three who has hepatitis C. In Brazil, hepatitis C is a full-fledged epidemic; over 1.5 million people are infected. In Rio alone there are thought to be over 110,000 cases—or 1.8 percent of the population—though more than 90 percent of cases are believed to be undiagnosed. Most people who contract the virus are unaware of the disease living inside them, as the hepatitis C virus can live inside of a host for years before exhibiting symptoms. Approximately 80 percent of hepatitis C cases will not manifest symptoms until the onset of liver failure.

The three women meet outside Cassia’s flat, a cramped apartment consisting of two rooms. Marcia introduces Andressa to Cassia, who had recently moved from another medical jurisdiction. Cassia and Marcia met only once before, when the former registered for medical care.

“We are coming here today to get to know you, since you’re a new patient that was transferred,” says Andressa. “I would like you to talk a bit about your life.”

“About the hepatitis?” Cassia asks.

“Yes, so we will be able to know a little bit about your history.”

Cassia discovered she had hepatitis while pregnant with her second child. During a routine exam, her blood work showed traces of the virus. “I never did blood transfusion,” she says. “I never used drugs or injectables, no tattoos at all. Nothing.”

Cassia most likely contracted the disease while working as a manicurist at a beauty salon. Unlike HIV, which cannot survive outside of a host’s body, HCV is a very resilient virus; it can stay alive and highly contagious for up to four days outside of a host.

Cassia knows that she has to stay vigilant or risk transmitting the disease. “You need to pay attention to everything,” she says, “even the [manicure] stick, even the glaze. Because if I work on your nails, and I cut your finger and pass the glaze over your blood and then I close the glaze in the bottle, all the disease, all the bacteria goes inside the bottle, proliferating. They are very happy in there.”

The doctor warned Cassia that the infection would change her lifestyle. “The doctor said that I would not be able to breastfeed,” says Cassia, “that I would not be able to do a natural childbirth, that I should avoid contact with people if I cut myself. No contact with children or with my husband. Sexual relations only with a condom. She gave me a lot of instructions.”

“At the time I thought I was going to die,” she remembers. “I was terrified. It was awful news, even worse because I was pregnant.” But when she went to follow up with a specialist at the University Hospital Gafrée e Guinle, her tests indicated that she had a low viral load. And each subsequent test indicated the same thing. Cassia decided to abandon the treatment, feeling confident that she was healthy and reluctant to make the long, inconvenient trip from Tabajaras to the hospital.

But during her third pregnancy, the virus appeared again in her blood work. “I thought, ‘I can’t believe it, I can’t accept it,’” says Cassia. “I was going to give birth in one week.” Her doctors told her to have the baby, and then follow up for exams after he was born. And that’s just what she did, six months after the birth of her son. “I received the results today,” Cassia tells them.

She goes inside and comes back holding a piece of paper. “It says I have so small a viral load that I cannot even say that I am a hepatitis C patient,” she exclaims, grinning as she raises her fist. “Yeah, victory!”

Just then, Cassia’s nine month-old son appears next to his mother, his brown locks rubbing against her leg. A small dribble of saliva rolls down his chubby cheeks. He claws at his mother with his tiny fingers, trying to get her attention.

Cassia looks down at her son and her smile fades, swallowing before she continues. “I can’t tell you if my children have hepatitis C or not,” she says. “The baby’s exams say that there is no virus. But I don’t know if my children got hepatitis C or not, if I passed it to them during the pregnancy or after, because I breastfed them.”

Marcia and Andressa, however, try to allay her fears. “We will schedule an appointment, we will follow you, we will do the exams to discard these possibilities about the two children,” Andressa assures her, her voice steady and purposeful. “This is the reason we are here. To give you this information.”

Approaching another patient’s home, Marcia calls out, “Antonia!”

A short bespectacled woman with auburn hair opens the glass door and hugs Marcia. Antonia is being treated for hypertension and Marcia visits her regularly. The two know each other well. “I am visited every fifteen days,” Antonia says smiling. “They are always coming!”

The three sit down on a leopard print couch, Antonia sandwiched between the two visitors. Marcia takes a clipboard out of her backpack and begins asking her patient questions while the nurse measures her blood pressure.

“Have you started your diet?” she asks.

“Yes,” Antonia replies in her tinny rasp.

“Are you sure?” Marcia asks knowingly, a smile on her face.

“There is no diet at all,” she admits, chuckling.

“Your blood pressure is higher than last time.”

“It’s because I didn’t take the medicine,” she admits again, tittering like a guilty child.

“She’s a rebel,” Marcia exclaims. “Do you want us to come here and feed it to you?” Marcia’s patients trust her enough to be honest with her. As a community agent, it is her job to make them feel comfortable talking about their personal lives, to discuss their problems, to tell the truth about what they are going through. That is why she is so effective.

“I put a lot of responsibility on myself because I know there are a lot of people who depend on me,” says Marcia. “But there are some things I just can’t know. I have to deal with a lot of things. Sometimes, patients pass away and I feel sad. But I like the work. Each day is different.”

Up the hill, a group of young boys are playing soccer on an outdoor concrete court, painted blue with yellow and white lines. Empty steel frames serve as nets. One of the kids kicks the ball and it bounces off the crossbeam into the air, caught by a green net that covers the open space. The soccer court is part of an unfinished project to build a sports center in the favela. Below, the structure is empty, with bits of rubble and trash heaped up a large pile of dirt.

“The structure is suffering the passage of time,” says Douglas, age 26. He is standing on the side of the court, smoking a cigarette and shouting encouragements to the kids.

“The court was built as part of a project, but it wasn’t finished,” he explains. “This is a very unstructured community. How can an old person live here past the age of 60? Without public light? And water and electricity? Only God can help us.”

Douglas was born and raised in Tabajaras. Like most of its residents, he works outside of the community, at an expensive restaurant in the Leblon area. He adjusts his baseball cap, keeping his eye on the game. “There is no water sometimes,” he says. “Sometimes I look at these houses and all the lights are off. And the general cleanliness of the community, I don’t like it. There’s a lot of garbage.”

But things aren’t all bad. “The health system is not perfect, but at least it works,” says Douglas. “If I needed to give them a score from 0 to 10, I’d give them a 4. It could be worse. Agents come once a week; they know everyone’s history. So when they go to a home, they already know everything about the patient.”

* * *

Sandra Guimaraes de Almeida is another of Marcia’s patients. She lives with her fiancée Rogerio in a one room apartment, part of a larger tenement structure they share with five other families. Rogerio is sick, lying on a mattress on the floor below the television, wrapped in a zebra-print blanket. Standing in their tiny kitchen, Sandra is tidying up and preparing tea.

“I’ve lived here for eight years,” says Sandra. “It is a very nice place, I like it. It’s a small thing, but it’s ours, thank god. And that’s it.”

Sandra was diagnosed with hepatitis C almost two years ago. She suspects that she contracted the virus during a manicure, but isn’t sure; prior to her diagnosis, Sandra hadn’t heard of the disease. “For me it was very worrying,” she says. “I became very nervous, because until then I knew nothing about the disease.“

After doing research, Sandra found out about interferon therapy, which is used to treat hepatitis C. The treatment has a success rate of about 45 percent. The side effects, however, are devastating. Patients experience severe depression, malaise, fever, chills, and muscle pains and aches. “The doctor invited [Rogerio] and I to watch a lecture explaining how the interferon affects people,” says Sandra. “The reactions it could cause in the body, things like depression, agony, discouragement, changes in humor, all of this. The treatment lasted six months. I had all these side effects. It was hard for me, it was very complicated.”

Rogerio helped Sandra get through the shock of diagnosis and pain of the treatment. “He is my rock,” she says, smiling over at Rogerio. “He is my base, my column. I never gave up because he always gave me strength.”

“After we found out about the disease, I was afraid he would want to break up with me. But instead, he proposed to me,” says Sandra, crying as she shows off the ring. “We are engaged, we are going to get married, and he is very good to me.”

Though her interferon regimen is over, Sandra still takes ribavirin, an anti-viral used to stem the reproduction of the hepatitis C virus. Without public healthcare, Sandra would not be able to afford the drug. “My doctor said the treatment is very expensive,” Sandra explains. “The other day [Rogerio] took the ribavirin by mistake, thinking it was an antibiotic. And then I explained to him ‘You can’t take this medicine, it is ribavirin, and I need to take it from the clinic.’ And our clinic doesn’t even receive the medicine. I have to get this medicine at other clinics downtown.”

The clinic that serves Tabajaras is in the heart of Copacabana, right next to the Siqueira Campos metro station. More than 100,000 people receive treatment there, though the Family Health Strategy only covers between twenty and thirty thousand. The goal is to expand coverage to the entire area, but priority is given to those communities that need the program most, like Tabajaras.

Dr. Anna Paula Borges Carrijo is the family doctor responsible for the Apoena team here at the clinic. She serves approximately 3,000 people, and must find a way to balance their needs with the resources at her disposal. “I think that the biggest problem is to discuss how to give the public the health that our population needs,” says Dr. Carrijo. “It is to guarantee the access...For example, I take care of three thousand people, and I have to see three hundred people a month. If we do a count, we will say that it takes ten months to see everyone in my community. But I don’t have that much time, because everybody wants to see me in one month. But it’s impossible to see three thousand people in one month.”

In order to effectively serve her community, Dr. Carrijo and her team have to prioritize cases according to a set of protocols. “To decide one thing is priority or not, we have to use [information],” she explains. “One of this is the probability of death and the other one is how vulnerable the person is or the family is. So in the discussions that our team has, we use both things to [assess] the case.”

In the case of a disease like hepatitis C, which does not manifest symptoms until it has progressed to a life-threatening state, this leaves room for error.

“In other countries like Canada or the UK or Spain,” says Dr. Carrijo, “[public healthcare] started [after the second world war], or in the UK [after the first world war]. And we have only twenty-five years of our health system in Brazil...I think that SUS, our public health system, is getting better because we believe in it and there are cities like Rio de Janiero that believe a lot in primary healthcare and are investing a lot of money to do it. And we are trying to construct this. But I think it can be much better.”